Written on May 8, 2020 by Gale Proulx

Category: Professional Development

Creativity for a data scientist means something much different than any given artistic field. For the field of Data Science, creativity sprouts from collaboration and unique solutions to a given problem. While solution to a machine learning problem could be a beautiful orchestration of math and business mindset combined to present a beautiful, informative visualization, there are limits. A writers world is much more relaxed on creative guidelines, which is what I find I struggle with when trying to write a creative piece.

The Limits of Data Science Creativity

The current status of data analysis is anything but exact. There is not scientific process that has been refined to address any given situation. Every use case of a common machine learning algorithm usually requires specific domain knowledge making it hard to nail down a common procedure. Every data scientist knows there will be some form of data collection, data exploration, data analysis, model building, and production deployment. This outline of a process seldom changes.

Unfortunately, this is just an outline. To have a defined process with a known specific timeline requires experience. There is no way around this. Obviously this is true for any practice, as you need experience to gauge how difficult a project will be and how long it will take. Data science unfortunately doesn’t have that accessible history built up yet. Companies are capitalizing on this lack of knowledge which makes for a great opportunity to make money. If a company can successfully implement data science services in a reliable and confident manner, they have a million dollar idea.

With all that being said, the outline still exists. A data scientist shouldn’t expect weird twists and turns. It should always be clear that the next steps are to take because there is an outline. After enough projects, a pattern (outline) is apparent and while there may be some changing variables, some things stay well grounded. Creativity tends to flow from how you deviate from the outline, not how you invent new algorithms or try outlandish exploration techniques.

The Limits of Writing

In stark contrast, writing follows a much broader outline. There are different genres which follow certain guidelines. Sci-Fi tends to have a strict grounding in the real world often presenting challenging ideas. Fantasy has elements of wonder and can stretch beyond real life concepts without rock solid explanations. Young Adult fiction tends to focus on relationships and relatable experiences without a defined objective for the main protagonist.

All pieces of writing are bound to the rules of the language. While it is okay to break rules, you have to do so deliberately or the work tends to look sloppy. There are limits to how long a book can be. Writing a 3,000 page fantasy novel would be too much.

There are a lot of limitations to what can be written, but these limits are meant to be broken. Lord of the Rings went haywire on creating a fantasy world that was so extensive it basically needed a dictionary of lore. Despite the drastic differences, Lord of the Rings it still in the same overarching genre as Eragon, which was not as extensive and much different.

The Struggle of a Data Scientist Writer

These guidelines for how to write any given piece of writing feels like a very similar structure to analyzing data, but there are two key differences: variability between projects and process.

When a data science project ends up being much more successful (accurate) than another similar project, there are usually some expected changes in how the machine learning model was built. Parameters might be hypertuned differently. Different models could be used. The data could be formatted in a different way. Optimizations could be tweaked to that specific problem. Beyond these modifications, not much else can happen. Granted, these few modifications can have drastic and very complex impacts on how a model learns, but the one thing being changed at the end is the model. A judge of how well a model performs is based on statistics, not readership.

For writing, this is obviously quite different. Books are vary to a much greater degree than a data science project: especially for a fantasy novel. The world will most likely be completely inconsistent from one story to the next. Rules about how that world operates will undoubtedly change. Even the laws of physics don’t have to be followed as long as there is some type of consistency. The outline for writing a fantasy novel is not enough to make a successful fantasy story. There needs to be some type of second outline, a barrier that the story is contained within. Lord of the Rings can’t have aliens coming down to Middle Earth wielding infinity stones. That would break its rules. Yet a fan fiction crossover could very well make the worlds of Lord of the Rings and Marvel collide and the piece could be widely popular.

At the end of the day, a novel’s success is dependent on response from other writers in the community, as well as a general fan base. As with any artistic work, if not a single person wants to look at your work, then it would be improper to call that work successful. (This does not mean it isn’t good work, it just means it doesn’t grab the attention it needs to be considered successful.)

Unintentional Creativity

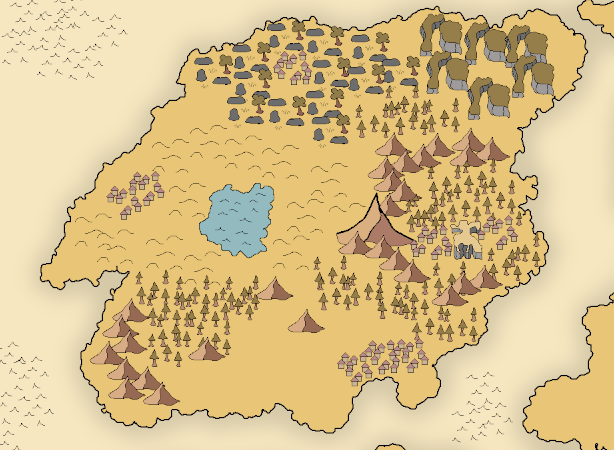

While I work on creating a world map, I find it hard to know what step is the next step to take as the outline is so general. I have added houses to symbolize towns, as shown below, but I find it hard to make this map meaningful. It is hard to force creativity and have spontaneous ideas about why a certain people would want to live in a tundra or a canyon. Lore needs to exist to be shown with a map, but I need to make a map to know where to start making the lore.

The chicken and the egg paradox presents itself over and over again throughout this project. Unfortunately, making a new fantasy world is not like hypertuning a model. You can’t systematically force yourself to have creativity. There is no grid search to optimize the lore you make. My best strategy thus far has been to allow these ideas to sit in the back of my brain and let them fester. When a creative moment strikes, I grab the nearest piece of paper and start recording notes to hold onto interesting ideas like the one below.