Written on May 15, 2020 by Gale Proulx

Category: Professional Development

One of the things that is not apparent in a large portion of the world of academia is how important documentation is. Smaller projects tend to have no need for documentation because the purpose of that small project is quite apparent. Programming assignments are often very focused on exploring one particular data structure or concept. The scope of a project tends to not breach multiple files. Additionally, the amount of time it takes to complete a homework assignment is never greater than one year. All of these factors make documentation at a small level quite useless as there is much work that needs to be done and never referenced again.

Ironically, in the workforce this is often not the case. Company projects almost always last longer than a year. In some cases, you may be working with code that was written when the company started. Most industries with long term projects have a reliance on previous work, and that work is often undocumented. This creates a very inefficient system where documentation is never made because it takes too much time, only encouraging worse practices for the future. In a worst case scenario, some jobs are created by the sheer lack of documentation.

While documentation is a time sink in the beginning that does not produce any short term benefits, the long term consequences can be very damaging to the lifespan thereafter of a company. This very consequence is what I am trying to avoid, hence why I have spent more time this week documenting than trying to creatively add new ideas to my book.

Setting Yourself Up for Success

When I started this project one week before graduation, the first thing I did was spend five hours deciding how I wanted to proceed in planning this project. The scale of this project, as mentioned previously, is quite large. From my previous experience trying to write this story for the past four years, I realized that I need an organization system that allows me to keep track of plot points and world development.

My first attempt at organizing a broader project timeline was to make a LibreOffice Calc spreadsheet as mentioned in my first post. While this did help with an overall project timeline, it wasn’t enough to organize all the details of the Unintentional Calamity Universe (UCU). All of my previous content surrounding the UCU was stored in one Microsoft Word document. While this did work fairly well at a smaller scale, it lacked a couple of key components.

The first flaw was no version tracking. Ideas are constantly being scrapped and brought back. My first solution was to add an idea graveyard where I could read about previous ideas. This was okay, but it made it hard to find older content, and I had to decide what to keep and what to delete.

The second flaw was searchability. Trying to find a reference or a town name was annoying. While Word does support headers and a table of contents, it just doesn’t have the same robustness of a programming documentation system.

The solution to all my problems for a proper, robust documentation system accidentally fell into my lap when I had a meeting about another project with my advisor Narine Hall.

GitBook

Apparently GitHub also has GitBook which is essentially a template website specifically focused on general documentation. This was perfect. While I do have the skills to code this website from scratch, buy a domain, and control everything through GitHub pages as I have done with this website, I don’t have the time. The scope of this project might start getting out of hand if I have to maintain multiple different websites.

GitBook offers version control, easy markdown editing, and a free URL under their domain. There is no back-end or front-end for me to worry about. In addition, it also addresses the two flaws of keeping track of a universe inside a Word document. Firstly, the version control provided by this service can help keep track of major changes, meanwhile a web page devoted to keeping track of smaller revisions will solve my initial issue of keeping track of what work I do. Secondly, the search function of this service is amazing. It has the capability of searching through all web pages not only looking at titles, headers, and subheaders, but it can also look through the contents of each page. The search bar is essentially a search engine just for your documentation. This functionality is exactly what I needed.

By pure chance, I found this new innovative tool and immediately implemented it. The new Unintentional Calamity Compendium can be found at this GitBook Page Link. Not only will the progress of this project be more visible, but it will be much easier to show to friends and editors what I’m working on.

Creative Progress

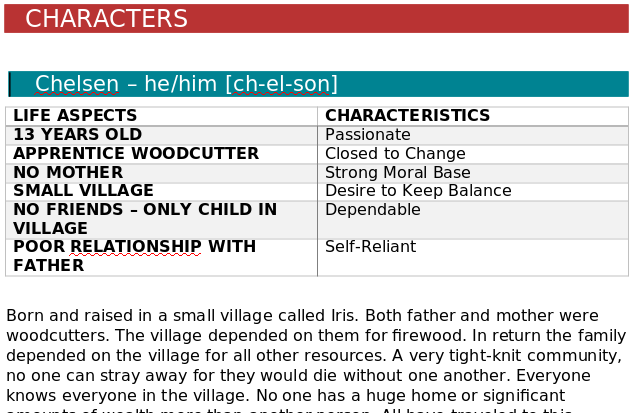

Making a switch from a text document to online documentation was a big step, but it was not the only piece of this project that I completed. To stay on track with the project timeline, I have added to the UCU. The history of the village of Iris has been flushed out which in turn also defined my magic system. I made progress on two objectives at once, which should help with my project timeline later down the line.

Not only did I get the chance to develop these systems, but I also had the chance to explain the idea to some friends. When I pitched my magic system to my roommates they immediately understood how the Schools of Reasoning (tied with the history of Iris) worked. I didn’t have to give them an example for them to immediately follow the logic. I also got some encouraging feedback when they said the system felt very logic and science oriented. This is the exact intended effect. If I had to guess, this might be the foundation on which I build these stories. There might be Star Trek and Doctor Who vibes throughout the series as I write it. I have accepted that this book will most likely end up being in the Fantasy genre, but it doesn’t mean I can’t twist the norm to be a Sci-Fi inspired Fantasy novel.

I’m excited to see what ideas come to my mind when I develop the next towns before next weeks deadlines.